Black Seminoles

A Historical Overview

By Katarina Wittich

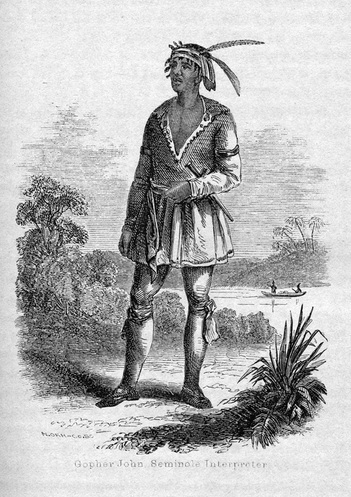

John Horse

John Horse

This is a brief review of the history of the Black Seminoles. There are several excellent books that go into this subject in depth. They may be found in the partial bibliography at the end of this article.

In many ways the history of the Black Seminoles is similar to the history of the United States. It's the story of a proud people whose refusal to be subjugated led them to become who they are today. They are an amalgam of many cultures and experiences.... a tapestry made richer by its contrasting colors and stronger by the countless trials it has been through.

The Black Seminoles have been known by a number of names. Historically they have been called Seminole Negroes, Indian Negroes, Seminole Freedmen and Afro-Seminoles. Today, in Mexico they are called Mascogos, in Oklahoma - Freedmen, and in Texas they will often just go by the term Seminole.

The Black Seminoles came into being during the 18th and 19th century as runaway slaves and free blacks from the eastern seaboard found their way south to join the Seminole Indians in Florida. The Seminoles themselves were a confederation of a number of different Native American bands that had been pushed south by the European expansion into their territories. Upper and Lower Creeks, Oconis, Apalachicolas and Mikasukis came together under one principal chief, but they maintained many of their separate customs and languages. To this day there are still two primary Seminole languages Hitchiti and Muskogee.

Into this loose alliance of tribes came freedmen and runaway slaves, escaping to Spanish Florida where slavery had been abolished. It is not known exactly in what capacity the newcomers joined the Seminoles. What is clear is that most of them lived in their own villages, kept their own livestock, had their own chiefs and seem to have been treated as equals by the Seminoles. While some of them intermarried with the Seminoles, and became culturally indistinguishable from the full blood Seminoles, most adopted Seminole customs but also kept their original African cultures along with the Afro-Baptist traditions that had been picked up during slavery.

They dressed largely like Southeastern Indians, wearing brightly colored hunting shirts, leggings and moccasins, with silver jewelry and turbans with plumes for special occasions. And they followed the Seminole practice of communal agriculture, working the land jointly and sharing the harvest. But their religious beliefs and customs, like their language, remained uniquely theirs a blend of African, Seminole and Christian. They drank tea, much like the Seminole black drink, as part of their communion services. They practiced the ring shout along with traditional Seminole dances. And they continued the West African practice of using day names for their children, such as Cudjo and Cuffy or their English translations: Monday and Friday. Some of them took on Seminole busk names, but unfortunately few of those have been recorded. In general it seems that they adapted rapidly and creatively to their new circumstances, fusing all their various influences into a new culture that would prove to be strong enough to provide support through all the hardships to come.

Sometime in the late 1700s the first references to Seminole Negroes as slaves to the Seminoles begin to appear. However, this was a very different form of slavery than that practiced by the Europeans. The Seminoles already had a tradition of their own in which captives from other Native American bands were called slaves and eventually were adopted into the tribe to replace members lost in war.

In the case of the Black Seminoles, at first the slavery appears to have been in name only, and may even have originally been adopted in order to protect black members of the band from white slavers who assumed that any black person without an owner was fair game. In any case, until removal to Indian Territory, the only effect that this "slavery" seems to have had on the Black Seminoles was that they were required to pay a tithe from the produce of their fields to their Seminole "owners".

Under this arrangement, the Black Seminoles prospered. They were excellent farmers as well as hunters and warriors. A number of observers in the early 1800's commented that the "Seminole Negroes" were wealthier than their supposed owners, with larger houses and flourishing fields of corn, rice and vegetables and livestock.

In addition to their success in agriculture, a number of Black Seminoles also attained prominence within the Seminole confederation as interpreters and warriors. Their experiences as slaves left them with a knowledge of the ways of the white men that made them invaluable as negotiators and military tacticians. Many of them spoke English and Spanish as well as Hitchiti or Muskogee. They also spoke their own language, sometimes called Siminol, a creole very similar to Gullah, made of a blend of African languages, English, Spanish and Muskogee. Interpreters like Abraham, Cudjo and John Horse became so influential in the Seminole confederation that whites complained that they were dictating policy, not just interpreting. General Thomas S. Jesup, who spent years fighting the Seminoles, said of them; "Throughout my operations I found the Negroes the most active and determined warriors; and during conference with the Indian Chiefs I ascertained that they exercised an almost controlling influence over them."

As warriors, the Black Seminoles were renowned for their skill and bravery, and were greatly valued as allies by the Seminoles. They were fighting for more than just land, they were fighting for survival and for their freedom, so they were uncompromising in their ferocity and tenacity. These skills were soon to be put to the test, as America turned a greedy eye on the rich lands of Spanish Florida.

During most of the 1700's the Seminoles and Black Seminoles had lived in relative peace despite the wars over the possession of Florida between Spain and Britain. However, by the early 1800's the United States was becoming covetous of the rich land that the Seminoles lived on, and southern slaveholders were becoming increasingly vocal about the dangers of allowing the Seminole/African alliance to continue. They rightly saw it as an invitation to their slaves to rebel and run away. In 1812 a group of American settlers, with the blessing of the U.S. Government, invaded Spanish East Florida. The Seminoles and Black Seminoles joined largely black troops fighting under the Spanish flag and temporarily repulsed the invaders. However, the alarm caused by the idea of armed blacks fighting against white soldiers spurred the American government to send larger forces, which were eventually successful at driving the Seminoles from their settlements in the Alachua region, leaving it open for white settlers. Although the Seminoles had been instrumental in keeping Florida in Spanish hands, they had lost their livestock and supplies and were forced to relocate on barren, unproductive land.

The next thirty years saw the Seminoles and Black Seminoles constantly engaged in fierce battles with the American government for their land and, in the case of the Black Seminoles, for their freedom from the American form of chattel slavery. Under the command of Andrew Jackson American troops repeatedly invaded Spanish and British Florida until in 1819 Spain ceded Florida to the United States. The Black Seminoles now were at even greater risk from slavers, as they no longer had the Spanish to protect them. Some left Florida altogether, making their way to Andros Island in the Bahamas, but most stayed and resettled again alongside the Seminoles in the swampy and infertile lands south of Tampa. There they managed to eke out a survival living, often forced to resort to raiding in order to get by.

The continued existence of a Black and Indian alliance was a big thorn in the side of the Southern states, as runaway slaves continued to head to Florida to join the Seminoles. In addition, the alliance was a problem for the federal government, who wanted to remove the Seminoles from Florida altogether and send them to reservations in Indian Territory, leaving their land open for white settlement. However, the Black Seminoles did not want to leave the relative safety of Florida for Indian Territory, where they would be sharing a reservation with Creek Indians. The Creeks were known to be active in the slave trade, aggressively kidnapping both free blacks and slaves for resale in the south. Many of the officials of the time period complained that it was the Black Seminoles that were preventing the Seminoles from removing. As the governor of Florida put it: "The slaves belonging to the Indians have a controlling influence over their masters and are utterly opposed to any change of residence."

So the government began a campaign to separate the two groups, offering the Seminoles rewards if they returned black members to their southern masters and refused safe haven to any new runaways. The Seminoles often agreed to these conditions, but never fulfilled them.

In 1830 the U.S. passed the Indian Removal Act and the attempts to get the Seminoles to move west intensified. Some bands signed treaties agreeing to move, but they were not authorized to represent the Seminoles as a whole. Nonetheless, the government insisted that the Seminoles had signed and must leave. The Seminoles refused to go and thus began the Second Seminole war. General Jesup, the commander of the government forces, stated that "This, you may be assured, is a Negro and not an Indian war; and if it be not speedily put down the south will feel the effects of it before next season." Obviously the government was being made very nervous by the Black Seminoles.

In all, there were three Seminole wars as the US government tried to force the Seminoles out of Florida. They were extremely costly and lengthy campaigns, and in the end the army was unable to defeat the Seminoles succeeding in persuading them to move only when General Jesup assured them safe passage and protection for their black members. This promise was one that that Jesup rapidly realized he could not keep. Many of the Black Seminoles were still legally the property of southern slaveholders, and the planters forced Jesup to agree to return to them all Black Seminoles who had been taken in battle. Furious at Jesup's betrayal, the Seminoles fought back. Under the leadership of War Chiefs Osceola, Wild Cat and John Horse they seized and liberated the hostages who had been surrendered under the terms of the truce. Faced with renewed hostilities, Jesup came up with a new policy. He promised the Black Seminoles freedom if they separated from the Indians and surrendered. But he didn't know what to do with them once free, so he proposed sending them to Indian Territory along with the Seminoles. This plan effectively ended Black Seminole resistance. It was better to risk Creek slavers as a free person than to continue the struggle as a slave. The change in policy drove a further wedge between the Black Seminoles and the Seminoles, who felt that they had been used and then abandoned and lost their property to boot.

Although the Seminoles and Black Seminoles fought hard and well together during the Seminole Wars, the seeds of dissension had been successfully planted and would take fruit in Indian Territory.

From the Seminole Wars a leader emerged who would shape the destiny of his people with great foresight and courage.

His name was John Horse, also known as Juan Caballo, John Cowaya, or Gopher John. He was born around 1812 in the Alachua Savanna and began his rise to prominence during the Second Seminole War as a warrior and interpreter or negotiator for Principal Chief Micanopy. He was leader of the Oklahawa band of Black Seminoles and appears to have been an astute businessman and farmer, amassing wealth far beyond that of the average Seminole. He spoke a number of languages and later on acted as interpreter for the US army as well as for the Seminoles. But in the early years he was one of the principal Black Seminoles leading the fight against removal. He was captured along with the famed warriors Osceola and Wild Cat under a false truce and imprisoned at Fort Marion in St. Augustine.

Horse and Wild Cat fasted until they were thin enough to slip through the bars on the roof of their cell and escape. Osceola had taken ill and he died soon afterward, leaving Wild Cat to inherit the mantle of War Chief. John Horse and Wild Cat became fighting and drinking companions, and brilliant leaders of their respective peoples. The bonds they forged during the wars would hold for the next twenty years as they led their people on an odyssey across the United States, from Florida to Oklahoma, to Mexico, in search of freedom and a better life.

In 1838, after many years of fighting fiercely against removal, most of the remaining Seminoles and Black Seminoles, including John Horse, gave themselves up for transport to Indian Territory. A key factor in this appears to have been Jessup's declaration that all blacks who surrendered would be given their freedom. In any case, John Horse was the last Black Seminole leader to surrender. For the next several years he worked as a negotiator for the government, helping to bring in the remaining Seminoles, including his friend Wild Cat, who was the last Seminole chief to come in. By 1842, all but several hundred Seminoles had been moved to Indian Territory and the Second Seminole war was over. It had cost the US over 20 million dollars, which was four times what the US paid Spain for Florida itself.

The U. S. launched a Third Seminole war in 1855, but they were unable to drive the remaining Seminoles out of the Florida swamps to which they had retreated. Descendants of the Seminoles and Black Seminoles who stayed in Florida still live there to this day.

The situation in which the Seminoles found themselves in Indian Territory was very unpleasant. They had been arbitrarily forced by the government to share a reservation with the Creeks, many of who were ancient enemies. They were numerically fewer than the Creeks and therefore had less power in the councils. They were given the less fertile land and were in danger of being forced to adapt to Creek customs. The Creeks were one of the more assimilated tribes. They had intermarried heavily with whites, and had adopted white forms of slavery and many white customs. For the traditional Seminoles, of which Wild Cat was a leader, this was unacceptable. And for the Black Seminoles it was extremely dangerous. As soon as they arrived in Indian Territory the Creeks began to raid, kidnapping Black Seminoles and selling them off to white slavers. John Horse's own sister, Juana, had two children stolen and sold. Despite best efforts and John Horse's money, they were never recovered. For a while the Black Seminoles stayed at Fort Gibson for protection by the army, but eventually they were forced to return to the reservation. There they settled in their own villages, as they always had, and started to rebuild a life. The first black settlement was Wewoka, which is still the heart of Black Seminole territory in Oklahoma today.

Wild Cat and his followers refused to accept Creek domination, so they camped temporarily on Cherokee land in protest. The rest of the Seminoles did the best they could on Creek land, but times were very hard and a lot of resentment developed between the Seminoles and Black Seminoles. Seminoles made several assassination attempts on John Horse's life, and he eventually had to move back to the fort for protection. It is possible that the Seminoles felt that as a negotiator for the army he was responsible for all the failed promises that the government made. There were rumors that the Seminole Council felt that he was too full of himself now that he was a free man. In 1845 the Seminoles signed a treaty that brought the tribe under Creek Law. That meant that it now was now longer legal for black members to bear arms, or live in their own villages, whether free or slave. This was too much for John Horse.

In 1845 and 1846 he made a number of trips to Washington DC to present his people's plight to President Polk. Horse appears to have gained access to the president, and to have had the support of none other than his former enemy, General Jesup, in asserting the unfairness of the treatment of the Black Seminoles. Jesup obviously felt responsible, as he had been the one who promised the Black Seminoles freedom upon surrender. But no one in the government was willing to do anything about it. Horse asked that his people be allowed to return to Florida, or transported to Africa, or sent anywhere other than Creek Territory.

Meanwhile the situation for the Black Seminoles in Indian Territory was becoming truly desperate as entire families were captured and sold and the Indian agent appeared to be encouraging the Creeks and Seminoles to do so. The Creeks also were complaining about the Black Seminoles, accusing them of theft and drunkenness and inciting slaves to run away and join them. Clearly the independence of the Black Seminoles was a threat to all slave owners; white or Native American.

Things were not much better for Wild Cat's band of Seminoles, or for the Seminoles in general. The reservation was lacking in game, it was much colder than the climate they were used to, and the lands were infertile and subject to drought. The Seminoles found themselves dependent on agency handouts and starving.

Then in 1848 Principal Chief Micanopy died. As Micanopy's sister's son, Wild Cat was directly in line in the matrilineal tradition to inherit the chieftaincy. Instead the council passed him over and selected Jumper, a proslavery, pro-Creek Chief who was close to the Indian Sub-Agent Marcellus Duvall, a known trafficker in slaves.

Wild Cat and John Horse had had enough. The Black Seminoles were at great risk whenever they were not directly under protection of the military, and the Creeks were threatening to enforce their slave codes if the Seminoles would not. With Jumper in power and the Indian Agent as his co-hort, Wild Cat had no hope of influencing matters much in the Seminole Council. So in November of 1849 the two men led their bands of followers out of the reservation on a one year trek to Mexico, where slavery was illegal and they had been promised land and supplies in return for becoming military colonists, protecting the borderlands against hostile Indian raids.

Through the next few years other groups of Black Seminoles would leave Indian Territory to follow them to Mexico, many suffering terrible casualties from Indians and slavers along the way. However, many Black Seminoles remained in Indian Territory, fighting off the depredations of Creeks and slavers. They continued to live in their own towns and nourish their own culture in the face of all hardships, but they never regained the status that they had once had in Florida. They have had to fight ceaselessly for their rights, and are still engaged in that battle today.

In Mexico, the new settlers faced a different set of hardships, but for the first time the Black Seminoles were truly free. They were still subject to raids from slavers, but the slavers had to come across the border to get at them and were seldom successful. And the Black Seminoles, or Mascogos, as they were called in Mexico, had plenty of neighbors to help defend their freedom. Their settlement in Nacimiento, in the state of Coahuila, actually consisted of three separate villages. On their way through Texas the group had added a band of several hundred Kickapoo Indians to their group, which consisted of around 200 Seminole and 200 Mascogos. Each of these bands eventually settled along the Sabinas River near the town of Santa Rosa, a few miles apart from each other. On arriving in Coahuila the colonists found that they had been preceded by a group of Creek blacks, mostly of the Warrior and Wilson families, and a family of Biloxi Indians. These groups eventually joined the Mascogos and became a prominent part of the community.

For the next twenty years the Mascogos lived in Mexico, defending the area against raiding Comanche, Lipan Apache and the occasional slaver. In return for their services they were awarded approximately 26 square miles of land, to be shared with the Seminoles and the Kickapoo. The settlements of the three groups still exist in Mexico today.

The arrangement with the Mexican Government was that the colonists would supply warriors to join the Mexican army in hunting down Indian raiding parties whenever they invaded Coahuila. Under the command of Capitan Juan de Dios Vidaurri (aka John Horse), the Mascogos were fierce in their defense of their adopted country, and were constantly singled out for praise by their superior officers. For a number of years the Mascogos and the Seminoles seem to have fought happily side by side, with the Mascogos once again prospering as they farmed. Many of the Mascogos were baptized in the Catholic Church and took on Spanish names, but they never dropped any of their old customs, merely adding another layer to their already complex culture.

Unfortunately, around 1856 tensions began to rise between the allies. The Seminoles felt that the Mascogos were not sending enough warriors into battle and not submitting themselves sufficiently to Wild Cat¹s authority. The Mexican Governor tried to smooth over these problems, warning the Mascogos that they must obey Wild Cat. The Mascogos replied that John Horse was their only chief and in his absence they reported to Captain Cuffy. It is true that the Mascogos were no longer supplying as many warriors as the Seminole were. They were excellent farmers and disliked being pulled away from their fields, while the Seminole had little attachment to the land, preferring hunting and raiding. The Mascogos also were worried about leaving their families alone for periods of time as the Texas slavers were infuriated by the existence of a colony of free blacks and made every effort to raid and capture them.

Then, in late 1856 smallpox hit Nacimiento, killing Wild Cat and devastating the Seminole community. The Mascogos were less hard hit. With Wild Cat gone the alliance between the Mascogos and the Seminoles became increasingly fragile.

That same year, the Seminole Nation had negotiated a treaty giving them their own reservation, separate from the Creeks. There was little reason for the Seminoles to remain in Mexico, so they slowly began to return to Indian Territory. With the departure of many of the Seminoles the Mascogos became more vulnerable to slave raids, and in 1859 the Mexican government moved most of them inland to Laguna de Parras, where it would be harder for the slavers to get at them.

By 1861 all of the Seminoles had returned to Indian Territory, ending the alliance with the Mascogos that had benefited them both for so many years. As a final irony, the Seminole Council had just signed a treaty supporting the Confederacy, so the returning Seminoles received a Confederate escort back to Indian Territory.

The 1860s were a turbulent time for the Mascogos in Mexico. Mexico itself was in constant political upheaval, exacerbated by the French invasion in 1864. Things were difficult for everyone in Coahuila. Indian raids made life miserable and there was conflict over land and livestock between the Mascogos and the Mexicans. In Nacimiento, the original band of Kickapoo had returned to their reservation in the U.S. and was replaced by a much larger band of Kickapoo who had no contract with the government and thus did not have to serve as military colonists. With the Seminole gone, the Mascogos were now the only warriors left to defend Coahuila from Indian raids. Mexico was no longer a comfortable place for the Mascogos, and with slavery abolished after the Civil War there was no reason for them to remain. In addition, there was a change in Seminole leadership in Indian Territory and the Black Seminoles were now welcome if they wanted to return. So the Mascogos began to consider returning to the U.S.

Meanwhile, in Texas, the border settlements were being devastated by Indian raids. It was so bad that the country was gradually being depopulated as settlers were killed or fled. One of the marauding bands was the group of Kickapoo who lived in Nacimiento and would raid into Texas and then return to the safety of the Santa Rosa Mountains. A series of forts had been built in Texas to help protect the settlers, but they were very ineffective against the Indian raids. So the government decided that the best way to stop the raiding was to invite the raiding Indians from Nacimiento back to the U.S. and put them on reservations where they could be controlled. The government assumed that the Mascogos were raiding along with the Kickapoo. So the army sent Captain Frank Perry from Fort Duncan to Santa Rosa to meet with the Indians and persuade them to return to the U.S. The Kickapoo refused to parley. But the Mascogo were ready to leave. John Horse was in Laguna Del Parras, so they sent Sub-Chief John Kibbetts to negotiate.

John Kibbetts and Captain Perry worked out an agreement whereby the Mascogos would cross over to Texas as a first stage in their resettlement to Indian Territory. While temporarily in Texas the able bodied men would serve as scouts for the United States Army, helping them to stop the Indian raids. The Mascogos were ideally suited for this job, as they had been doing it for twenty years on the other side of the border.

In addition to standard payment for their services the government agreed to provide the Scouts with rations for their families, farming equipment, livestock and pay for their relocation to permanent land grants that the Indian Bureau would arrange in Indian Territory. No physical copy of this agreement has been found, but it is very clear that many promises were made to the Black Seminoles that were never kept.

On July 4th of 1870 the first group of Mascogos crossed back into Texas. Eventually most of the Mascogos would return to the U.S., leaving a small community in Nacimiento with whom they would retain close ties throughout the years.

In August of 1870 the first unit of the "Seminole Negro Indian Scouts" was mustered in at Fort Duncan in Eagle Pass under Major Zenas Bliss. He described the Mascogos as "Negroes (having) all the habits of the Indians. They were excellent hunters and trailers and splendid fighters." For the first time the army had a contingent actually capable of fighting against the Indians using Indian tactics. However, for the first three years the army didn't make much use of the scouts because of their inherent prejudices against anything unrecognizable by army protocol. A short account of an incident with the scouts from the diary of Captain Orsemus Boyd shows both the scouts amazing skills and the army prejudices that kept them from being used fully.

At four o'clock one morning, a Seminole Indian, attached to the command, brought me intelligence that six hours previously six horses, four lodges, one sick Indian, five squaws, and several children had descended into the canyon one mile above us and were then lost to sight. I asked:

"Had they provisions?"

"Yes, corn and buffalo meat."

"How do you know?"

"Because I saw corn scattered upon one side of the trail and flies had

gathered upon a piece of buffalo meat on the other."

"How do you know that one of the Indians is sick?"

"Because the lodge poles were formed into a travois, that was drawn by a

horse blind in one eye."

"How do you know the horse was half blind?"

"Because, while all the other horses grazed upon both sides of the trail,

this one ate only the grass that grew up upon one side."

"How do you know that the sick one was a man?"

"Because when a halt was made all the women gathered around him."

"Of what tribe are they?"

"Of a Kiowa tribe."

And thus, with no ray of intelligence upon his stolid face, the Seminole Indian stood before me and told all I wished to know concerning our new neighbors, whom he had never seen. Two hours later Captain Boyd found the group of Kiowas, just as the scout had described them.

By 1873 most of the scouts had been moved from Fort Duncan to Fort Clark, where they settled their families in an encampment along the Los Moras River, near Brackettville. Their duties so far had been routine, guarding livestock and performing escort services. The officers assigned to them complained of their lack of military manner and unwillingness to conform to the rules. However, in March of 1873 the situation improved when they were assigned a new kind of officer. Lieutenant John Lapham Bullis was a fighting Quaker who had commanded black troops during the civil war and was immediately able to see the value of the Scouts fighting and tracking skills despite their disregard for army procedure. He was a fighter of the same sort that they were, able to go for days without rations or sleep, fighting with the same stealth and flexibility as the Indians they were chasing. As one of his scouts put it "His men was on equality too. He didn't stand back and say "Go yonder", He say, "Come on, boys, let's go get em". In Bullis, the scouts found a commander that they could trust, and together they became an almost unbeatable combination. In eight years of relentless combat with the Indians they lost not one single man in battle. And they were instrumental in ending the Indian and outlaw raids in that section of Texas.

However, the story in the Black Seminole community was not so pretty. The promised supplies and land grants were slow in materializing, rations were minimal, and it was difficult to support all the members of the various groups on just the scouts' salaries. Many of the Mascogo were destitute and the Army and the Bureau of Indian affairs were taking turns denying responsibility for subsisting them or giving them the land and supplies they had been promised. At one point it seemed as if the Bureau of Indian Affairs was about to give them land in Indian Territory, when suddenly some bureaucrat discovered that they were black, and therefore could not be Indians and were not entitled to Indian land! Later, the government again agreed to give them land on the Seminole reservation, but, unwilling to share tribal benefits, the Seminole Chief refused to acknowledge them as members of his Nation.

Despite the desperate situation of their families, the Scouts continued to prove themselves heroic in battle and uncanny as trackers and scouts. The records show constant petitioning for their rights by their commanding officers, particularly Lt. Bullis and Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie. Almost every major officer they worked under spoke of their courage, battle skills, and the outrage of their being denied what they had been promised.

Then a new ruling denied rations to anyone but the men who were actually serving as scouts. Out of a community of over 200 people the scouts never numbered more than 50 men. The situation became impossible. The elderly and families without a scout in them to depend on were literally starving. Without adequate land and supplies to farm, camping temporarily on the army reservation, they had no way to feed themselves. Some resorted to petty thievery, occasionally stealing a stray cow. It must be understood that in the Texas of this time prominent white men had made their fortunes by rounding up stray cattle and branding them as their own. But if a Mascogo took one it was theft and they were liable for prosecution.

Against this ugly backdrop, the scouts performed feats of incredible bravery and skill. They worked hard and long hours together, survived great deprivations and were usually victorious. Four out of the 50 scouts were even awarded Congressional Medals of Honor for their bravery.

John Horse never enlisted in the scouts; instead he spent his last years on diplomacy, trying to get the U.S. government to honor its promises to his people. Then, in the summer of 1876, there was an assassination attempt on his life. There appears to have been no attempt to find the culprit. Possibly it was irate citizens who didn't want the Mascogos cultivating the land along the lush Los Moras River, or others who disliked Horse's insubordinate attitude. The ironic thing about this period is that while certain of Brackettville's citizens were swearing out complaints that the Mascogos were thieves, other equally upstanding citizens were requesting that the army enlist the rest of the available Mascogos as scouts in order to form a larger command under Lt. Bullis to keep them safe from bandits and hostile Indians.

John Horse was badly wounded in the assassination attempt and never fully recovered. The Mascogo community was infuriated by the attack and a number of them soon accompanied John Horse back to Nacimiento. Horse died in 1882 in Mexico City, immediately after successfully securing paper documentation to prove the Mascogos rights to the land in Nacimiento which they hold to this day thanks to his efforts.

The Scouts were not so lucky. By 1881, with their help, Texas had been made safe for settlers and they were no longer needed for combat. Bullis moved on to other assignments and the scouts once again went back to digging ditches. They were never given land in Indian Territory or elsewhere, despite the vehement protests of the officers they had worked under. Many of the Mascogos lived in extreme poverty some of the original scouts died as paupers. Over the years the numbers of scouts enlisted dwindled, and eventually in 1914 the scouts were disbanded. The 207 Black Seminoles still living on the military reservation of Fort Clark were summarily forced from their homes. Only a few of the oldest ones were allowed to remain. After 44 years of valiant service, the scouts and their families had been rewarded with little more than a subsistence living and broken promises. Their essential role in ending the Indian raids in South Texas ever acknowledged.

Today, there are Black Seminoles living in every section of the United States. The heaviest concentrations are still in Oklahoma, Texas, Florida and Coahuila, Mexico. They can also be found as far away as Andros Island in the Bahamas. They are a remarkable people resilient, resourceful and rich in culture and attitude. Elders in most areas still speak the Afro-Seminole Creole which embodies the diverse strands of their heritage from the last four hundred years. The Black Seminoles represent the best of America, this grand melting pot that brings us together, creating out of many peoples an amalgam that is stronger and more beautiful for its very differences.

E-mail comments and questions are welcome at [email protected]

In many ways the history of the Black Seminoles is similar to the history of the United States. It's the story of a proud people whose refusal to be subjugated led them to become who they are today. They are an amalgam of many cultures and experiences.... a tapestry made richer by its contrasting colors and stronger by the countless trials it has been through.

The Black Seminoles have been known by a number of names. Historically they have been called Seminole Negroes, Indian Negroes, Seminole Freedmen and Afro-Seminoles. Today, in Mexico they are called Mascogos, in Oklahoma - Freedmen, and in Texas they will often just go by the term Seminole.

The Black Seminoles came into being during the 18th and 19th century as runaway slaves and free blacks from the eastern seaboard found their way south to join the Seminole Indians in Florida. The Seminoles themselves were a confederation of a number of different Native American bands that had been pushed south by the European expansion into their territories. Upper and Lower Creeks, Oconis, Apalachicolas and Mikasukis came together under one principal chief, but they maintained many of their separate customs and languages. To this day there are still two primary Seminole languages Hitchiti and Muskogee.

Into this loose alliance of tribes came freedmen and runaway slaves, escaping to Spanish Florida where slavery had been abolished. It is not known exactly in what capacity the newcomers joined the Seminoles. What is clear is that most of them lived in their own villages, kept their own livestock, had their own chiefs and seem to have been treated as equals by the Seminoles. While some of them intermarried with the Seminoles, and became culturally indistinguishable from the full blood Seminoles, most adopted Seminole customs but also kept their original African cultures along with the Afro-Baptist traditions that had been picked up during slavery.

They dressed largely like Southeastern Indians, wearing brightly colored hunting shirts, leggings and moccasins, with silver jewelry and turbans with plumes for special occasions. And they followed the Seminole practice of communal agriculture, working the land jointly and sharing the harvest. But their religious beliefs and customs, like their language, remained uniquely theirs a blend of African, Seminole and Christian. They drank tea, much like the Seminole black drink, as part of their communion services. They practiced the ring shout along with traditional Seminole dances. And they continued the West African practice of using day names for their children, such as Cudjo and Cuffy or their English translations: Monday and Friday. Some of them took on Seminole busk names, but unfortunately few of those have been recorded. In general it seems that they adapted rapidly and creatively to their new circumstances, fusing all their various influences into a new culture that would prove to be strong enough to provide support through all the hardships to come.

Sometime in the late 1700s the first references to Seminole Negroes as slaves to the Seminoles begin to appear. However, this was a very different form of slavery than that practiced by the Europeans. The Seminoles already had a tradition of their own in which captives from other Native American bands were called slaves and eventually were adopted into the tribe to replace members lost in war.

In the case of the Black Seminoles, at first the slavery appears to have been in name only, and may even have originally been adopted in order to protect black members of the band from white slavers who assumed that any black person without an owner was fair game. In any case, until removal to Indian Territory, the only effect that this "slavery" seems to have had on the Black Seminoles was that they were required to pay a tithe from the produce of their fields to their Seminole "owners".

Under this arrangement, the Black Seminoles prospered. They were excellent farmers as well as hunters and warriors. A number of observers in the early 1800's commented that the "Seminole Negroes" were wealthier than their supposed owners, with larger houses and flourishing fields of corn, rice and vegetables and livestock.

In addition to their success in agriculture, a number of Black Seminoles also attained prominence within the Seminole confederation as interpreters and warriors. Their experiences as slaves left them with a knowledge of the ways of the white men that made them invaluable as negotiators and military tacticians. Many of them spoke English and Spanish as well as Hitchiti or Muskogee. They also spoke their own language, sometimes called Siminol, a creole very similar to Gullah, made of a blend of African languages, English, Spanish and Muskogee. Interpreters like Abraham, Cudjo and John Horse became so influential in the Seminole confederation that whites complained that they were dictating policy, not just interpreting. General Thomas S. Jesup, who spent years fighting the Seminoles, said of them; "Throughout my operations I found the Negroes the most active and determined warriors; and during conference with the Indian Chiefs I ascertained that they exercised an almost controlling influence over them."

As warriors, the Black Seminoles were renowned for their skill and bravery, and were greatly valued as allies by the Seminoles. They were fighting for more than just land, they were fighting for survival and for their freedom, so they were uncompromising in their ferocity and tenacity. These skills were soon to be put to the test, as America turned a greedy eye on the rich lands of Spanish Florida.

During most of the 1700's the Seminoles and Black Seminoles had lived in relative peace despite the wars over the possession of Florida between Spain and Britain. However, by the early 1800's the United States was becoming covetous of the rich land that the Seminoles lived on, and southern slaveholders were becoming increasingly vocal about the dangers of allowing the Seminole/African alliance to continue. They rightly saw it as an invitation to their slaves to rebel and run away. In 1812 a group of American settlers, with the blessing of the U.S. Government, invaded Spanish East Florida. The Seminoles and Black Seminoles joined largely black troops fighting under the Spanish flag and temporarily repulsed the invaders. However, the alarm caused by the idea of armed blacks fighting against white soldiers spurred the American government to send larger forces, which were eventually successful at driving the Seminoles from their settlements in the Alachua region, leaving it open for white settlers. Although the Seminoles had been instrumental in keeping Florida in Spanish hands, they had lost their livestock and supplies and were forced to relocate on barren, unproductive land.

The next thirty years saw the Seminoles and Black Seminoles constantly engaged in fierce battles with the American government for their land and, in the case of the Black Seminoles, for their freedom from the American form of chattel slavery. Under the command of Andrew Jackson American troops repeatedly invaded Spanish and British Florida until in 1819 Spain ceded Florida to the United States. The Black Seminoles now were at even greater risk from slavers, as they no longer had the Spanish to protect them. Some left Florida altogether, making their way to Andros Island in the Bahamas, but most stayed and resettled again alongside the Seminoles in the swampy and infertile lands south of Tampa. There they managed to eke out a survival living, often forced to resort to raiding in order to get by.

The continued existence of a Black and Indian alliance was a big thorn in the side of the Southern states, as runaway slaves continued to head to Florida to join the Seminoles. In addition, the alliance was a problem for the federal government, who wanted to remove the Seminoles from Florida altogether and send them to reservations in Indian Territory, leaving their land open for white settlement. However, the Black Seminoles did not want to leave the relative safety of Florida for Indian Territory, where they would be sharing a reservation with Creek Indians. The Creeks were known to be active in the slave trade, aggressively kidnapping both free blacks and slaves for resale in the south. Many of the officials of the time period complained that it was the Black Seminoles that were preventing the Seminoles from removing. As the governor of Florida put it: "The slaves belonging to the Indians have a controlling influence over their masters and are utterly opposed to any change of residence."

So the government began a campaign to separate the two groups, offering the Seminoles rewards if they returned black members to their southern masters and refused safe haven to any new runaways. The Seminoles often agreed to these conditions, but never fulfilled them.

In 1830 the U.S. passed the Indian Removal Act and the attempts to get the Seminoles to move west intensified. Some bands signed treaties agreeing to move, but they were not authorized to represent the Seminoles as a whole. Nonetheless, the government insisted that the Seminoles had signed and must leave. The Seminoles refused to go and thus began the Second Seminole war. General Jesup, the commander of the government forces, stated that "This, you may be assured, is a Negro and not an Indian war; and if it be not speedily put down the south will feel the effects of it before next season." Obviously the government was being made very nervous by the Black Seminoles.

In all, there were three Seminole wars as the US government tried to force the Seminoles out of Florida. They were extremely costly and lengthy campaigns, and in the end the army was unable to defeat the Seminoles succeeding in persuading them to move only when General Jesup assured them safe passage and protection for their black members. This promise was one that that Jesup rapidly realized he could not keep. Many of the Black Seminoles were still legally the property of southern slaveholders, and the planters forced Jesup to agree to return to them all Black Seminoles who had been taken in battle. Furious at Jesup's betrayal, the Seminoles fought back. Under the leadership of War Chiefs Osceola, Wild Cat and John Horse they seized and liberated the hostages who had been surrendered under the terms of the truce. Faced with renewed hostilities, Jesup came up with a new policy. He promised the Black Seminoles freedom if they separated from the Indians and surrendered. But he didn't know what to do with them once free, so he proposed sending them to Indian Territory along with the Seminoles. This plan effectively ended Black Seminole resistance. It was better to risk Creek slavers as a free person than to continue the struggle as a slave. The change in policy drove a further wedge between the Black Seminoles and the Seminoles, who felt that they had been used and then abandoned and lost their property to boot.

Although the Seminoles and Black Seminoles fought hard and well together during the Seminole Wars, the seeds of dissension had been successfully planted and would take fruit in Indian Territory.

From the Seminole Wars a leader emerged who would shape the destiny of his people with great foresight and courage.

His name was John Horse, also known as Juan Caballo, John Cowaya, or Gopher John. He was born around 1812 in the Alachua Savanna and began his rise to prominence during the Second Seminole War as a warrior and interpreter or negotiator for Principal Chief Micanopy. He was leader of the Oklahawa band of Black Seminoles and appears to have been an astute businessman and farmer, amassing wealth far beyond that of the average Seminole. He spoke a number of languages and later on acted as interpreter for the US army as well as for the Seminoles. But in the early years he was one of the principal Black Seminoles leading the fight against removal. He was captured along with the famed warriors Osceola and Wild Cat under a false truce and imprisoned at Fort Marion in St. Augustine.

Horse and Wild Cat fasted until they were thin enough to slip through the bars on the roof of their cell and escape. Osceola had taken ill and he died soon afterward, leaving Wild Cat to inherit the mantle of War Chief. John Horse and Wild Cat became fighting and drinking companions, and brilliant leaders of their respective peoples. The bonds they forged during the wars would hold for the next twenty years as they led their people on an odyssey across the United States, from Florida to Oklahoma, to Mexico, in search of freedom and a better life.

In 1838, after many years of fighting fiercely against removal, most of the remaining Seminoles and Black Seminoles, including John Horse, gave themselves up for transport to Indian Territory. A key factor in this appears to have been Jessup's declaration that all blacks who surrendered would be given their freedom. In any case, John Horse was the last Black Seminole leader to surrender. For the next several years he worked as a negotiator for the government, helping to bring in the remaining Seminoles, including his friend Wild Cat, who was the last Seminole chief to come in. By 1842, all but several hundred Seminoles had been moved to Indian Territory and the Second Seminole war was over. It had cost the US over 20 million dollars, which was four times what the US paid Spain for Florida itself.

The U. S. launched a Third Seminole war in 1855, but they were unable to drive the remaining Seminoles out of the Florida swamps to which they had retreated. Descendants of the Seminoles and Black Seminoles who stayed in Florida still live there to this day.

The situation in which the Seminoles found themselves in Indian Territory was very unpleasant. They had been arbitrarily forced by the government to share a reservation with the Creeks, many of who were ancient enemies. They were numerically fewer than the Creeks and therefore had less power in the councils. They were given the less fertile land and were in danger of being forced to adapt to Creek customs. The Creeks were one of the more assimilated tribes. They had intermarried heavily with whites, and had adopted white forms of slavery and many white customs. For the traditional Seminoles, of which Wild Cat was a leader, this was unacceptable. And for the Black Seminoles it was extremely dangerous. As soon as they arrived in Indian Territory the Creeks began to raid, kidnapping Black Seminoles and selling them off to white slavers. John Horse's own sister, Juana, had two children stolen and sold. Despite best efforts and John Horse's money, they were never recovered. For a while the Black Seminoles stayed at Fort Gibson for protection by the army, but eventually they were forced to return to the reservation. There they settled in their own villages, as they always had, and started to rebuild a life. The first black settlement was Wewoka, which is still the heart of Black Seminole territory in Oklahoma today.

Wild Cat and his followers refused to accept Creek domination, so they camped temporarily on Cherokee land in protest. The rest of the Seminoles did the best they could on Creek land, but times were very hard and a lot of resentment developed between the Seminoles and Black Seminoles. Seminoles made several assassination attempts on John Horse's life, and he eventually had to move back to the fort for protection. It is possible that the Seminoles felt that as a negotiator for the army he was responsible for all the failed promises that the government made. There were rumors that the Seminole Council felt that he was too full of himself now that he was a free man. In 1845 the Seminoles signed a treaty that brought the tribe under Creek Law. That meant that it now was now longer legal for black members to bear arms, or live in their own villages, whether free or slave. This was too much for John Horse.

In 1845 and 1846 he made a number of trips to Washington DC to present his people's plight to President Polk. Horse appears to have gained access to the president, and to have had the support of none other than his former enemy, General Jesup, in asserting the unfairness of the treatment of the Black Seminoles. Jesup obviously felt responsible, as he had been the one who promised the Black Seminoles freedom upon surrender. But no one in the government was willing to do anything about it. Horse asked that his people be allowed to return to Florida, or transported to Africa, or sent anywhere other than Creek Territory.

Meanwhile the situation for the Black Seminoles in Indian Territory was becoming truly desperate as entire families were captured and sold and the Indian agent appeared to be encouraging the Creeks and Seminoles to do so. The Creeks also were complaining about the Black Seminoles, accusing them of theft and drunkenness and inciting slaves to run away and join them. Clearly the independence of the Black Seminoles was a threat to all slave owners; white or Native American.

Things were not much better for Wild Cat's band of Seminoles, or for the Seminoles in general. The reservation was lacking in game, it was much colder than the climate they were used to, and the lands were infertile and subject to drought. The Seminoles found themselves dependent on agency handouts and starving.

Then in 1848 Principal Chief Micanopy died. As Micanopy's sister's son, Wild Cat was directly in line in the matrilineal tradition to inherit the chieftaincy. Instead the council passed him over and selected Jumper, a proslavery, pro-Creek Chief who was close to the Indian Sub-Agent Marcellus Duvall, a known trafficker in slaves.

Wild Cat and John Horse had had enough. The Black Seminoles were at great risk whenever they were not directly under protection of the military, and the Creeks were threatening to enforce their slave codes if the Seminoles would not. With Jumper in power and the Indian Agent as his co-hort, Wild Cat had no hope of influencing matters much in the Seminole Council. So in November of 1849 the two men led their bands of followers out of the reservation on a one year trek to Mexico, where slavery was illegal and they had been promised land and supplies in return for becoming military colonists, protecting the borderlands against hostile Indian raids.

Through the next few years other groups of Black Seminoles would leave Indian Territory to follow them to Mexico, many suffering terrible casualties from Indians and slavers along the way. However, many Black Seminoles remained in Indian Territory, fighting off the depredations of Creeks and slavers. They continued to live in their own towns and nourish their own culture in the face of all hardships, but they never regained the status that they had once had in Florida. They have had to fight ceaselessly for their rights, and are still engaged in that battle today.

In Mexico, the new settlers faced a different set of hardships, but for the first time the Black Seminoles were truly free. They were still subject to raids from slavers, but the slavers had to come across the border to get at them and were seldom successful. And the Black Seminoles, or Mascogos, as they were called in Mexico, had plenty of neighbors to help defend their freedom. Their settlement in Nacimiento, in the state of Coahuila, actually consisted of three separate villages. On their way through Texas the group had added a band of several hundred Kickapoo Indians to their group, which consisted of around 200 Seminole and 200 Mascogos. Each of these bands eventually settled along the Sabinas River near the town of Santa Rosa, a few miles apart from each other. On arriving in Coahuila the colonists found that they had been preceded by a group of Creek blacks, mostly of the Warrior and Wilson families, and a family of Biloxi Indians. These groups eventually joined the Mascogos and became a prominent part of the community.

For the next twenty years the Mascogos lived in Mexico, defending the area against raiding Comanche, Lipan Apache and the occasional slaver. In return for their services they were awarded approximately 26 square miles of land, to be shared with the Seminoles and the Kickapoo. The settlements of the three groups still exist in Mexico today.

The arrangement with the Mexican Government was that the colonists would supply warriors to join the Mexican army in hunting down Indian raiding parties whenever they invaded Coahuila. Under the command of Capitan Juan de Dios Vidaurri (aka John Horse), the Mascogos were fierce in their defense of their adopted country, and were constantly singled out for praise by their superior officers. For a number of years the Mascogos and the Seminoles seem to have fought happily side by side, with the Mascogos once again prospering as they farmed. Many of the Mascogos were baptized in the Catholic Church and took on Spanish names, but they never dropped any of their old customs, merely adding another layer to their already complex culture.

Unfortunately, around 1856 tensions began to rise between the allies. The Seminoles felt that the Mascogos were not sending enough warriors into battle and not submitting themselves sufficiently to Wild Cat¹s authority. The Mexican Governor tried to smooth over these problems, warning the Mascogos that they must obey Wild Cat. The Mascogos replied that John Horse was their only chief and in his absence they reported to Captain Cuffy. It is true that the Mascogos were no longer supplying as many warriors as the Seminole were. They were excellent farmers and disliked being pulled away from their fields, while the Seminole had little attachment to the land, preferring hunting and raiding. The Mascogos also were worried about leaving their families alone for periods of time as the Texas slavers were infuriated by the existence of a colony of free blacks and made every effort to raid and capture them.

Then, in late 1856 smallpox hit Nacimiento, killing Wild Cat and devastating the Seminole community. The Mascogos were less hard hit. With Wild Cat gone the alliance between the Mascogos and the Seminoles became increasingly fragile.

That same year, the Seminole Nation had negotiated a treaty giving them their own reservation, separate from the Creeks. There was little reason for the Seminoles to remain in Mexico, so they slowly began to return to Indian Territory. With the departure of many of the Seminoles the Mascogos became more vulnerable to slave raids, and in 1859 the Mexican government moved most of them inland to Laguna de Parras, where it would be harder for the slavers to get at them.

By 1861 all of the Seminoles had returned to Indian Territory, ending the alliance with the Mascogos that had benefited them both for so many years. As a final irony, the Seminole Council had just signed a treaty supporting the Confederacy, so the returning Seminoles received a Confederate escort back to Indian Territory.

The 1860s were a turbulent time for the Mascogos in Mexico. Mexico itself was in constant political upheaval, exacerbated by the French invasion in 1864. Things were difficult for everyone in Coahuila. Indian raids made life miserable and there was conflict over land and livestock between the Mascogos and the Mexicans. In Nacimiento, the original band of Kickapoo had returned to their reservation in the U.S. and was replaced by a much larger band of Kickapoo who had no contract with the government and thus did not have to serve as military colonists. With the Seminole gone, the Mascogos were now the only warriors left to defend Coahuila from Indian raids. Mexico was no longer a comfortable place for the Mascogos, and with slavery abolished after the Civil War there was no reason for them to remain. In addition, there was a change in Seminole leadership in Indian Territory and the Black Seminoles were now welcome if they wanted to return. So the Mascogos began to consider returning to the U.S.

Meanwhile, in Texas, the border settlements were being devastated by Indian raids. It was so bad that the country was gradually being depopulated as settlers were killed or fled. One of the marauding bands was the group of Kickapoo who lived in Nacimiento and would raid into Texas and then return to the safety of the Santa Rosa Mountains. A series of forts had been built in Texas to help protect the settlers, but they were very ineffective against the Indian raids. So the government decided that the best way to stop the raiding was to invite the raiding Indians from Nacimiento back to the U.S. and put them on reservations where they could be controlled. The government assumed that the Mascogos were raiding along with the Kickapoo. So the army sent Captain Frank Perry from Fort Duncan to Santa Rosa to meet with the Indians and persuade them to return to the U.S. The Kickapoo refused to parley. But the Mascogo were ready to leave. John Horse was in Laguna Del Parras, so they sent Sub-Chief John Kibbetts to negotiate.

John Kibbetts and Captain Perry worked out an agreement whereby the Mascogos would cross over to Texas as a first stage in their resettlement to Indian Territory. While temporarily in Texas the able bodied men would serve as scouts for the United States Army, helping them to stop the Indian raids. The Mascogos were ideally suited for this job, as they had been doing it for twenty years on the other side of the border.

In addition to standard payment for their services the government agreed to provide the Scouts with rations for their families, farming equipment, livestock and pay for their relocation to permanent land grants that the Indian Bureau would arrange in Indian Territory. No physical copy of this agreement has been found, but it is very clear that many promises were made to the Black Seminoles that were never kept.

On July 4th of 1870 the first group of Mascogos crossed back into Texas. Eventually most of the Mascogos would return to the U.S., leaving a small community in Nacimiento with whom they would retain close ties throughout the years.

In August of 1870 the first unit of the "Seminole Negro Indian Scouts" was mustered in at Fort Duncan in Eagle Pass under Major Zenas Bliss. He described the Mascogos as "Negroes (having) all the habits of the Indians. They were excellent hunters and trailers and splendid fighters." For the first time the army had a contingent actually capable of fighting against the Indians using Indian tactics. However, for the first three years the army didn't make much use of the scouts because of their inherent prejudices against anything unrecognizable by army protocol. A short account of an incident with the scouts from the diary of Captain Orsemus Boyd shows both the scouts amazing skills and the army prejudices that kept them from being used fully.

At four o'clock one morning, a Seminole Indian, attached to the command, brought me intelligence that six hours previously six horses, four lodges, one sick Indian, five squaws, and several children had descended into the canyon one mile above us and were then lost to sight. I asked:

"Had they provisions?"

"Yes, corn and buffalo meat."

"How do you know?"

"Because I saw corn scattered upon one side of the trail and flies had

gathered upon a piece of buffalo meat on the other."

"How do you know that one of the Indians is sick?"

"Because the lodge poles were formed into a travois, that was drawn by a

horse blind in one eye."

"How do you know the horse was half blind?"

"Because, while all the other horses grazed upon both sides of the trail,

this one ate only the grass that grew up upon one side."

"How do you know that the sick one was a man?"

"Because when a halt was made all the women gathered around him."

"Of what tribe are they?"

"Of a Kiowa tribe."

And thus, with no ray of intelligence upon his stolid face, the Seminole Indian stood before me and told all I wished to know concerning our new neighbors, whom he had never seen. Two hours later Captain Boyd found the group of Kiowas, just as the scout had described them.

By 1873 most of the scouts had been moved from Fort Duncan to Fort Clark, where they settled their families in an encampment along the Los Moras River, near Brackettville. Their duties so far had been routine, guarding livestock and performing escort services. The officers assigned to them complained of their lack of military manner and unwillingness to conform to the rules. However, in March of 1873 the situation improved when they were assigned a new kind of officer. Lieutenant John Lapham Bullis was a fighting Quaker who had commanded black troops during the civil war and was immediately able to see the value of the Scouts fighting and tracking skills despite their disregard for army procedure. He was a fighter of the same sort that they were, able to go for days without rations or sleep, fighting with the same stealth and flexibility as the Indians they were chasing. As one of his scouts put it "His men was on equality too. He didn't stand back and say "Go yonder", He say, "Come on, boys, let's go get em". In Bullis, the scouts found a commander that they could trust, and together they became an almost unbeatable combination. In eight years of relentless combat with the Indians they lost not one single man in battle. And they were instrumental in ending the Indian and outlaw raids in that section of Texas.

However, the story in the Black Seminole community was not so pretty. The promised supplies and land grants were slow in materializing, rations were minimal, and it was difficult to support all the members of the various groups on just the scouts' salaries. Many of the Mascogo were destitute and the Army and the Bureau of Indian affairs were taking turns denying responsibility for subsisting them or giving them the land and supplies they had been promised. At one point it seemed as if the Bureau of Indian Affairs was about to give them land in Indian Territory, when suddenly some bureaucrat discovered that they were black, and therefore could not be Indians and were not entitled to Indian land! Later, the government again agreed to give them land on the Seminole reservation, but, unwilling to share tribal benefits, the Seminole Chief refused to acknowledge them as members of his Nation.

Despite the desperate situation of their families, the Scouts continued to prove themselves heroic in battle and uncanny as trackers and scouts. The records show constant petitioning for their rights by their commanding officers, particularly Lt. Bullis and Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie. Almost every major officer they worked under spoke of their courage, battle skills, and the outrage of their being denied what they had been promised.

Then a new ruling denied rations to anyone but the men who were actually serving as scouts. Out of a community of over 200 people the scouts never numbered more than 50 men. The situation became impossible. The elderly and families without a scout in them to depend on were literally starving. Without adequate land and supplies to farm, camping temporarily on the army reservation, they had no way to feed themselves. Some resorted to petty thievery, occasionally stealing a stray cow. It must be understood that in the Texas of this time prominent white men had made their fortunes by rounding up stray cattle and branding them as their own. But if a Mascogo took one it was theft and they were liable for prosecution.

Against this ugly backdrop, the scouts performed feats of incredible bravery and skill. They worked hard and long hours together, survived great deprivations and were usually victorious. Four out of the 50 scouts were even awarded Congressional Medals of Honor for their bravery.

John Horse never enlisted in the scouts; instead he spent his last years on diplomacy, trying to get the U.S. government to honor its promises to his people. Then, in the summer of 1876, there was an assassination attempt on his life. There appears to have been no attempt to find the culprit. Possibly it was irate citizens who didn't want the Mascogos cultivating the land along the lush Los Moras River, or others who disliked Horse's insubordinate attitude. The ironic thing about this period is that while certain of Brackettville's citizens were swearing out complaints that the Mascogos were thieves, other equally upstanding citizens were requesting that the army enlist the rest of the available Mascogos as scouts in order to form a larger command under Lt. Bullis to keep them safe from bandits and hostile Indians.

John Horse was badly wounded in the assassination attempt and never fully recovered. The Mascogo community was infuriated by the attack and a number of them soon accompanied John Horse back to Nacimiento. Horse died in 1882 in Mexico City, immediately after successfully securing paper documentation to prove the Mascogos rights to the land in Nacimiento which they hold to this day thanks to his efforts.

The Scouts were not so lucky. By 1881, with their help, Texas had been made safe for settlers and they were no longer needed for combat. Bullis moved on to other assignments and the scouts once again went back to digging ditches. They were never given land in Indian Territory or elsewhere, despite the vehement protests of the officers they had worked under. Many of the Mascogos lived in extreme poverty some of the original scouts died as paupers. Over the years the numbers of scouts enlisted dwindled, and eventually in 1914 the scouts were disbanded. The 207 Black Seminoles still living on the military reservation of Fort Clark were summarily forced from their homes. Only a few of the oldest ones were allowed to remain. After 44 years of valiant service, the scouts and their families had been rewarded with little more than a subsistence living and broken promises. Their essential role in ending the Indian raids in South Texas ever acknowledged.

Today, there are Black Seminoles living in every section of the United States. The heaviest concentrations are still in Oklahoma, Texas, Florida and Coahuila, Mexico. They can also be found as far away as Andros Island in the Bahamas. They are a remarkable people resilient, resourceful and rich in culture and attitude. Elders in most areas still speak the Afro-Seminole Creole which embodies the diverse strands of their heritage from the last four hundred years. The Black Seminoles represent the best of America, this grand melting pot that brings us together, creating out of many peoples an amalgam that is stronger and more beautiful for its very differences.

E-mail comments and questions are welcome at [email protected]

Partial Bibliography

Books:

(The two most complete on the history of the Black Seminoles are Freedom on the Border by Kevin Mulroy and The Black Seminoles from the papers of Kenneth Porter - edited by Amos and Senter)

Boyd, Mrs.Orsemus B. Cavalry Life in Tent and Field. New York: Selwin Tait and Sons 1894

Burton, Arthur T. Black, Red and Deadly: Black and Indian Gunfighters of the Indian Territory, 1870-1907. Austin: Eakin Press, 1991

Carter, Robert G. The Old Sergeants Story: Winning The West from the Indians and Bad Men in 1870 to 1876 New York: Fred H. Hitchcock, 1926

On the Border with Mackenzie or Winning the West from the Comanches. New York: Antiqquarian Press, 1961 (1935)

Creel, Margaret Washington. A Peculiar People: Slave Religion and Community Culture Among the Gullahs. New York: New York University Press, 1988

Hancock, Ian F. The Texas Seminoles and their Language. Austin: University of Texas African and Afro-American Studies and Research Center, 1980

Howard, James H. in collaboration with Willie Lena Oklahoma Seminoles: Medicines, Magic, and Religion. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1984

Latorre, Felipe A. And DoloresL. Latorre. The Mexican Kickapoo Indians. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1976

Leckie, William H. The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Negro Cavalry in the West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1967

Montgomery, Cora. Eagle Pass; Or, Life on the Border. New York: Putnams Semi Monthly Library for Travellers and the Fireside 1852

Mulroy, Kevin. Freedom on the Border. The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila and Texas. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 1993

Mulroy, Kevin The Seminole Freedmen: A History. Race and Culture in the American West Series: University of Oklahoma Press 2007

Pingenot, Ben E. Paso del Aguila: A Chronicle of Frontier Days on the Texas Border as Recorded in the Memoirs of Jesse Sumpter, 1827-1910. Austin: Encino Press, 1969

Pirtle, Caleb III and Michael F. Cusack. The Lonely Sentinel. Fort Clark: On Texas’ Western Frontier. Austin: Eakin Press, 1985

Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. The Negro on the American Frontier. New York: New York Times and Arno Press, 1971

Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom Seeking People. Revised and edited by Alcione M. Amos and Thomas P. Senter. Gainsville: University Press of Florida, 1996

Sobel, Mechal. Trabelin’ On: The Slave Journey to an Afro Baptist Faith. Westport Ct. Princeton University Press, 1979

Thompson, Richard A. Crossing the Border with the 4th Cavalry: Mackenzie’s Raid into Mexico, 1873. Waco, Texas: Texian Press, 1986

Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro American Art and Philosophy. New York: Random House, 1983

Wallace, Ernest. Ranald S. Mackenzie on the Texas Frontier. Lubbock: West Texas Musseum Assoc. 1965

Books:

(The two most complete on the history of the Black Seminoles are Freedom on the Border by Kevin Mulroy and The Black Seminoles from the papers of Kenneth Porter - edited by Amos and Senter)

Boyd, Mrs.Orsemus B. Cavalry Life in Tent and Field. New York: Selwin Tait and Sons 1894

Burton, Arthur T. Black, Red and Deadly: Black and Indian Gunfighters of the Indian Territory, 1870-1907. Austin: Eakin Press, 1991

Carter, Robert G. The Old Sergeants Story: Winning The West from the Indians and Bad Men in 1870 to 1876 New York: Fred H. Hitchcock, 1926

On the Border with Mackenzie or Winning the West from the Comanches. New York: Antiqquarian Press, 1961 (1935)

Creel, Margaret Washington. A Peculiar People: Slave Religion and Community Culture Among the Gullahs. New York: New York University Press, 1988

Hancock, Ian F. The Texas Seminoles and their Language. Austin: University of Texas African and Afro-American Studies and Research Center, 1980

Howard, James H. in collaboration with Willie Lena Oklahoma Seminoles: Medicines, Magic, and Religion. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1984

Latorre, Felipe A. And DoloresL. Latorre. The Mexican Kickapoo Indians. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1976

Leckie, William H. The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Negro Cavalry in the West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1967

Montgomery, Cora. Eagle Pass; Or, Life on the Border. New York: Putnams Semi Monthly Library for Travellers and the Fireside 1852

Mulroy, Kevin. Freedom on the Border. The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila and Texas. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 1993

Mulroy, Kevin The Seminole Freedmen: A History. Race and Culture in the American West Series: University of Oklahoma Press 2007

Pingenot, Ben E. Paso del Aguila: A Chronicle of Frontier Days on the Texas Border as Recorded in the Memoirs of Jesse Sumpter, 1827-1910. Austin: Encino Press, 1969

Pirtle, Caleb III and Michael F. Cusack. The Lonely Sentinel. Fort Clark: On Texas’ Western Frontier. Austin: Eakin Press, 1985

Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. The Negro on the American Frontier. New York: New York Times and Arno Press, 1971

Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom Seeking People. Revised and edited by Alcione M. Amos and Thomas P. Senter. Gainsville: University Press of Florida, 1996

Sobel, Mechal. Trabelin’ On: The Slave Journey to an Afro Baptist Faith. Westport Ct. Princeton University Press, 1979

Thompson, Richard A. Crossing the Border with the 4th Cavalry: Mackenzie’s Raid into Mexico, 1873. Waco, Texas: Texian Press, 1986

Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro American Art and Philosophy. New York: Random House, 1983

Wallace, Ernest. Ranald S. Mackenzie on the Texas Frontier. Lubbock: West Texas Musseum Assoc. 1965